Eric Hammesfahr: Shakespeare, Swords, and the Smithsonian

Many of our students show interest in careers in the arts. Fortunately for them, we had the opportunity to hear from Eric Hammesfahr, a museum specialist at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington, DC, about how he came to work in the field.

Contents

An Interest Is Born

In high school, Mr. Hammesfahr was interested in art, theater, and writing–he loved to draw, paint, and sculpt, and he enjoyed trying new things to challenge himself. He also took advantage of the chance that he had to work backstage in his high school’s theater program. Describing that time of his life, Mr. Hammesfahr says that part of the pull of backstage work was that he “felt a kinship with these [fellow backstage workers]; dedicated people who come together to tell a story. I didn’t know it then, but storytelling was going to be a huge part of my life.”

College Years

After high school Mr. Hammesfahr went to Washington College in Maryland, thinking that he would write fiction and, perhaps, also create art. As he talked with our WTMA students, he shared that one of the reasons he selected this particular college was because he wanted to have a “campus” experience, and this school had spread-out buildings, a large green, a social center for literary students, and all the idyllic norms that he had grown to expect of “college.” By the end of his first year, though, Mr. Hammesfahr realized that he wasn’t the best writer and was instead more suited towards the visual arts. After meeting with his English advisor and viewing some art school pamphlets, he found himself drawn to The Corcoran School of the Arts and Design, in Washington, DC. Though he was somewhat fearful of the new city environment, he made the leap and transferred schools.

Creating Art For The Shakespeare Theatre Company

For the four years he attended the Corcoran, Mr. Hammesfahr honed his craft in painting. After graduating, he spent a few years in DC painting artistically for pleasure and painting houses for profit. Eventually, he made a contact who introduced him to some folks in the theater world and he began to work with The Shakespeare Theatre Company. At this point, Eric thought that he had, again, “found his people.” He was employed with The Shakespeare Theatre as a props painter/sculptor, and he spent the next ten years painting, sculpting, and creating strange and innumerable props for over thirty different productions. Describing this experience, Mr. Hammesfahr says, “You have to be flexible, because what a bunch of actors and a director might think works great on Tuesday morning, will have to be something else entirely by Tuesday night. I love the challenges, such as ‘We need an octopus that can be thrown at another actor, that will not hurt them, that will last being thrown night after night, and… it has to look real, and we have to be able to clean it.’” Just to show you how talented Mr. Hammesfahr is, take a look at some of the incredible artifacts he created:

Here is an Apostate sword that had to A) look like a sword, and B) be able to bend in a decidedly un-swordly way. The final product is made out of foam and fiberglass.

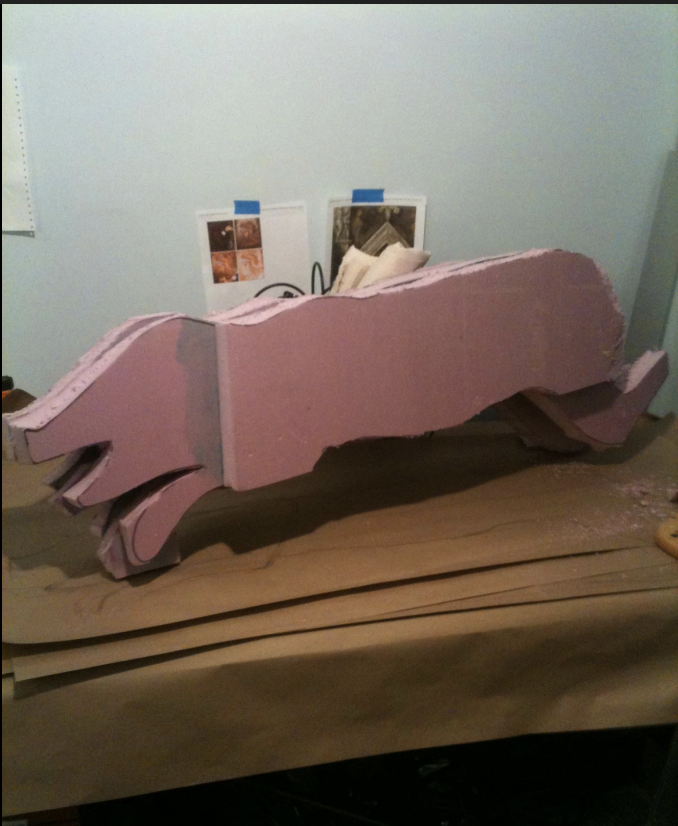

In order to carve artifacts, Mr. Hammesfahr typically glues together layers of pink foam into a rough base shape, and then carves them down into the more nuanced form that will become the final product. Check out how he made this pig!

A statue of Queen Victoria Mr. Hammesfahr created was fashioned out of carved foam and draped fabric that was painted a beautiful shade of red, making it look like a genuine piece from 1900s England. After the production for which she was created had come and gone, the lovely queen was relegated to the woods behind Mr. Hammesfahr’s shop. Unfortunately, during a police chase that would make its way through Mr. Hammesfahr’s backyard, Queen Victoria had guns drawn on her and, at the mercy of scoundrels, was eventually set afire by unknown assailants.

When working on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, Mr. Hammesfahr created a statue of the Virgin Mary, first carving it out of glued layers of foam. The end product looks amazingly realistic!

For a performance with a pop art feel, Mr. Hammersfahr recreated Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen’s Spoonbridge and Cherry sculpture (on a smaller scale) along with Jeff Koons’s balloon dog in a cage.

Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

Mr. Hammesfahr grew to enjoy making molds and special effects, and figuring out how to make things “grosser, lighter, and more beautiful.” However, even though he loved his job, he felt he had outgrown his work. Taking advantage of his network of artist friends, Mr. Hammesfahr heard about and applied for a job at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History & Culture as an exhibit fabricator. The idea of working for a museum, and for a museum representing the African American experience, sounded amazing to Mr. Hammesfahr. However, he knew he would have to work hard to make this opportunity a reality, and he had to weigh heavily the unknown risks of taking a new job against the potential benefits it offered. Ultimately, he got the position and made the move into museum work.

Mr. Hammesfahr says, “the transition from theater [to museum work] was a huge learning curve. Unlike theater, everything I created has to be perfect because the standards for the museum are very high, and people look at things more closely. As an exhibit fabricator, I had to learn how to conduct myself in a gallery space around valuable objects. I had to memorize every part of the museum to see if anything was out of place or damaged.” Mr. Hammesfahr and his team have to make sure that the museum always looks right before the doors open at 10 AM.

Creating Displays for Precious Works

He still gets to make amazing things even though his job is so different. Here is a brass mount he created for this very fragile and historic nineteenth-century washboard. Part of his job is to always keep in consideration what materials are going to be the safest for the museum piece for the longest period of time. Exhibit fabricators frequently rely on brass, acrylic, and plexiglass, because they don’t rub off on the objects.

Another mount Mr. Hammesfahr made was for a trumpet. The hope with this mounting is that in using the brass and displaying the trumpet upright, it looks almost as if this artifact is floating. The mount is nearly invisible!

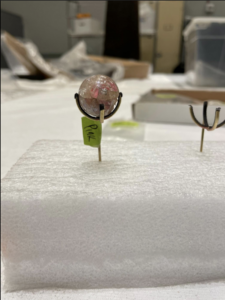

A tiny mount for an eighteenth-century marble showcases just how fragile some of these pieces really are.

Even more contemporary artifacts deserve time and attention when being mounted. Mr. Hammesfahr showed us an image of one of Kobe Bryant’s jerseys. Originally installed flat, the jersey was deinstalled and reinstalled on a mannequin form to infuse it with life (see featured image at top).

Mr. Hammesfahr’s current job engages him creatively, and allows him to problem solve in many of the same ways that he has done for so many of his previous jobs. He says “I’ve been lucky to have a career doing what I’m good at, developing skills along the way, and working with truly excellent people.” However, he’s not sure what’s next, and he thinks that’s a good thing. “Follow your passions and creativity,” he implores. Here at the Academy, we think that’s a great message to pass along to students considering just what their next five (or twenty-five!) years might look like.